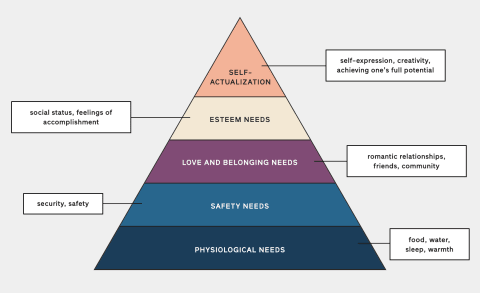

Maslow originally presented the hierarchy of needs broken down into five categories, based on what he believed to be most to least pressing. Later his theory became popularly depicted in a pyramid format. These are categories, organized from the “lowest tier” of needs to the “highest.” In Maslow’s books Motivation and Personality and Religions, Values, and Peak Experiences, he expanded on the tiers of human needs. He first introduced the ideas of cognitive needs and aesthetic needs as essential to the hierarchy of needs, and then finally he brought the concept of transcendence needs into the picture. Viktor Sander, a social skills counselor, explains that “there are too many unanswered questions to set up a rigorous scientific test. How do you know when a need is fully gratified? How can you tell which needs at a given level you should measure? When does someone move up a level?” One study conducted from 2005 to 2010 of 60,865 participants across 123 countries attempted to show just this. Participants answered a series of questions about needs lined up with Maslow’s hierarchy. The results demonstrated that, as previously stated, there are certain needs that are universal, but meeting those basic needs was not necessary in order to satisfy those that Maslow considered less critical. The theory also assumes people will act completely based on their needs. “Today we know that we humans don’t just act on our needs,” elaborates Sander. “We do many things that go entirely against our needs. How do you use Maslow’s theory of needs to explain a monk or nun burning themselves to death in protest?” This is just the beginning of the criticism Maslow’s hierarchy has faced. Daramus implores us to think about it even from a job perspective. The act of taking a job you love over one that’s higher-paying but less enticing defies this hierarchical nature as well. When you take emotion out of the equation, of course the lower needs would be met first, but as humans are far from emotionless, this is not how it works in actuality. For example, Maslow’s hierarchy implies that people who don’t have stable access to food and housing (i.e., poor people) don’t care as much about belonging, self-esteem, and self-actualization. It implies that creative expression, personal achievement, and self-betterment are things only desired and dreamed of by the rich. This is, of course, not true. Some researchers have traced the origin of the pyramid to consulting psychologist Charles McDermid. He used the pyramid in a 1960 article to describe the theory, and it took off from there. When looked at as a guide to our varied needs instead of a designated order in which they must be met, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs can still hold relevance in today’s society. Each person has different priorities and reasons to go after certain needs, possibly at the expense of their others. This flexibility is part of our individuality and determines how each of us moves forward through life, figuring out our needs and all.